How do you make sure your research reaches as large an audience as possible? How can you become a more visible researcher? There are a number of tips you can follow. We’ve linked below to a number of interesting pieces that might just help you get more readers and get yourself more widely known. It’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Search Engine Optimisation

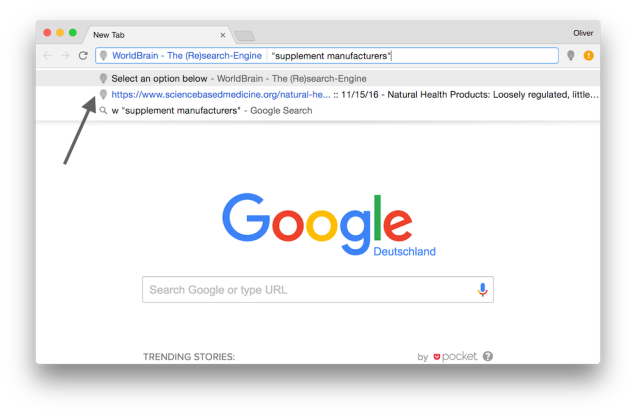

Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) is the process of maximising the number of visitors to a website by ensuring that it appears at the top/close to the top on a list of results returned by a search engine. This is usually a process used by businesses to find new customers. Websites higher up the list of results usually get more traffic and potentially more business. But SEO isn’t just something that those in marketing should know about. Researchers can learn a few lessons from this too to ensure their research appears either top or close to the top on results from search engines.

Anne-Marie Green has some useful advice for how authors can optimise their research, such as using relevant keywords and using them frequently and appropriately. Elsevier, one of the largest global publishers, also extol the benefits of SEO. Chris Grieves echoes these suggestions in a blog post and provides some really helpful tips for how to select keywords. Grieves also recommends ways to select journal article titles to make them discoverable. LSE’s excellent Impact Blog suggests more ideas in its essential ‘how to’ guide for choosing journal article titles.

Abstracts

Abstracts are short, yet powerful statements that introduce a longer article. These paragraphs often convince a reader whether it is worth their time reading the entire article. So the impact you make with an abstract is pivotal. You might find conflicting advice on what makes a good abstract. Emerald suggests a succinct statement of no more than 250 words. LSE’s Impact Blog suggests 200-350 words and gives greater detail on what an abstract should include. However, Times Higher Education recently featured an article that flew in the face of recommended advice. Research undertaken at the University of Chicago of scientific papers suggested shorter abstracts meant fewer reads. Their advice was more is more. On the other hand, perhaps brevity is key when giving your article a title.

Be An Active Online Researcher

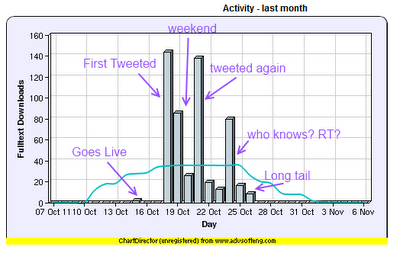

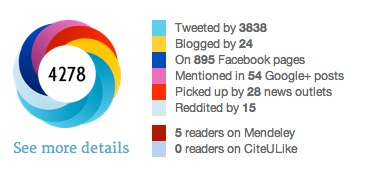

When your research is published in an academic journal, the publisher will do promote it themselves and libraries and researchers around the world will have access. But it’s easy to forget the most important person in promoting your research: you. Having an active online researcher profile can do wonders for promoting your research. Utrecht University provides a wealth of information, including the actions you can take as a researcher to become more visible and how to use Google Scholar Citations. The University of Leeds also gives advice, such as making research outputs open access and making data shareable where possible. On the Altmetric blog, Fran Davies echoes these, but also suggests using blogs and Twitter to promote research and taking advantage of collaborative and networking opportunities.

We’ll be going into some more of these, such as Altmetrics, in more detail in future blog posts.

References

Davies, F. (2015) Tips and tricks: how to promote your research successfully online. Available at: http://www.altmetric.com/blog/tips-and-tricks-how-to-promote-your-research-successfully-online/?hootPostID=9fc46f1295b289c3f7bd59b1e008e91c (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

Else, H. (2015) Scientists: ignore the rules on writing to get citations. Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/content/scientists-ignore-rules-writing-get-citations (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

Elsevier Biggerbrains (2012) Get found – optimize your research articles for search engines. Available at: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/get-found-optimize-your-research-articles-for-search-engines (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

Emerald (n.d.) How to…write an abstract. Available at: http://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/authors/guides/write/abstracts.htm (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

Green, A. (2013) Search engine optimization and your journal article: do you want the bad news first? Available at: http://exchanges.wiley.com/blog/2013/07/23/search-engine-optimization-and-your-journal-article-do-you-want-the-bad-news-first/ (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

Grieves, C. (2015) Maximising the exposure of your research: search engine optimisation and why it matters. Available at: https://methodsblog.wordpress.com/2015/12/18/seo/ (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

LSE Impact Blog (2011) Your essential ‘how to’ guide to choosing article titles. Available at: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2011/06/21/your-essential-%E2%80%98how-to%E2%80%99-guide-to-choosing-article-titles/ (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

LSE Impact Blog (2011) Your essential ‘how to’ guide to writing good abstracts. Available at: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2011/06/20/essential-guide-writing-good-abstracts/ (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

Reisz, M. (2015) Should I keep the title of my paper brief? Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/should-i-keep-title-my-paper-brief (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

University of Leeds (2014) Raise your research profile. Available at: https://library.leeds.ac.uk/researcher-citations (Accessed: 10 February 2016)

Utrecht University (2015) Research impact and visibility. Available at: http://libguides.library.uu.nl/researchimpact/profiles (Accessed: 10 February 2016)